An Abundance Agenda for Education

Like many, I’m caught up in the Abundance bonanza. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson make a persuasive case that America’s most pressing problems stem not from a lack of resources, but from a shortage of permission - particularly the way the progressive policy makers lose focus on outcomes in favor of process. The book focuses on how to build in three key areas — housing, clean energy, infrastructure.

Klein and Thompson trace the intellectual history of the argument, in part, to Annie Lowery’s terrific The Great Affordability Crisis, a seminal piece in 2020 raising the alarm of the increasing accessibility of housing, healthcare, and education for many Americans. While education didn’t make the final cut in Abundance, there is a strong case for an abundance agenda.

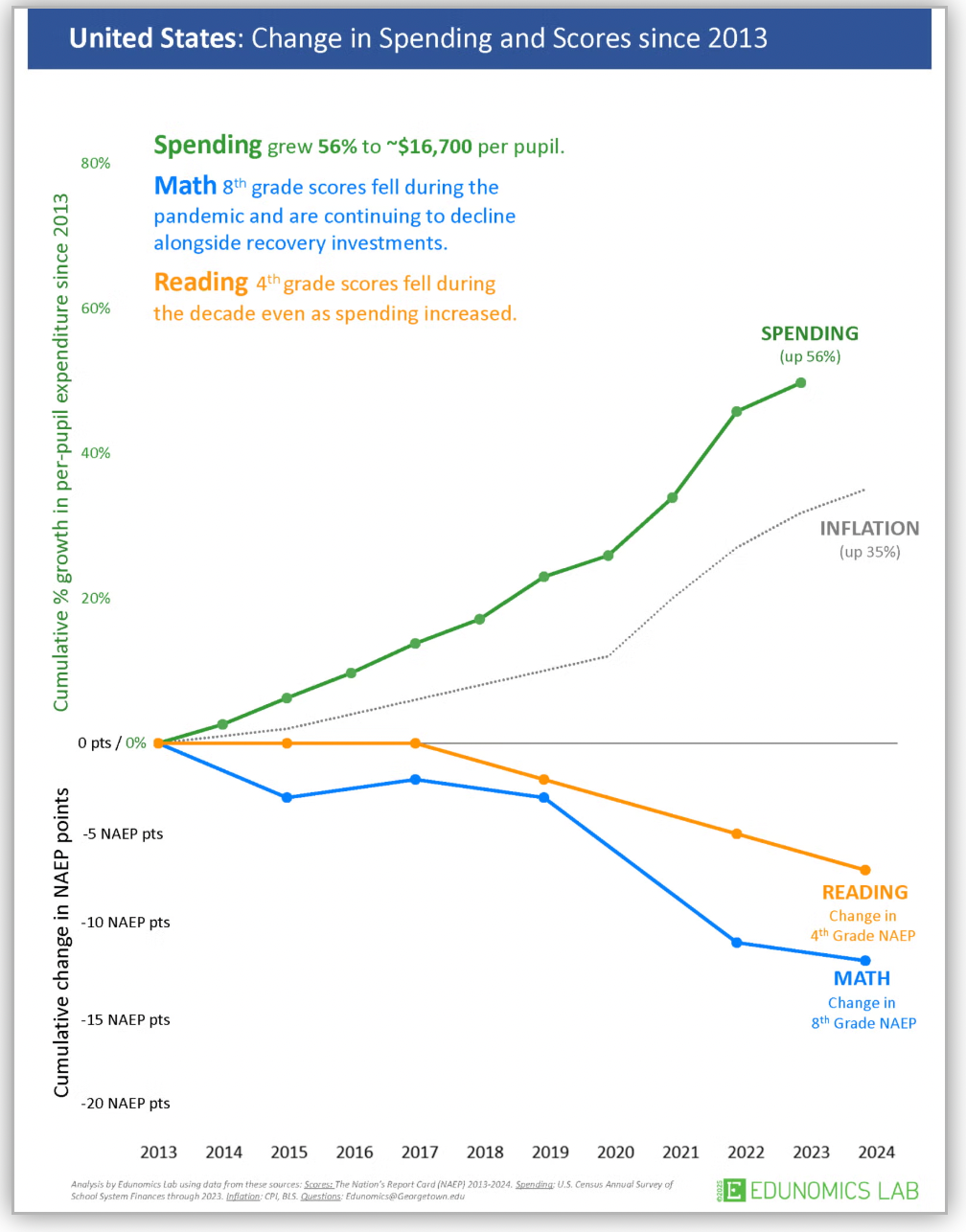

The United States spends over $800 billion annually on public education — a figure that rivals the GDP of some nations — yet we find ourselves stuck in place. Achievement gaps persist, teacher shortages grow, and parents of all income levels express frustration with the one-size-fits-all model of schooling. If abundance means producing more of what works, then education is crying out for an abundance agenda of its own — one that embraces pluralism in delivery and pluralism in measurement.

We need more schools. More precisely, we need more types of schools — small, agile, responsive institutions that reflect the diversity of student needs and family priorities. Enter the microschool.

Microschools are small, often independently operated educational settings — typically between 5 and 50 students — that blend personalized learning with strong community ties. Some use online curriculum, others adopt Montessori or classical models, and many serve neurodiverse or non-traditional learners. They are not constrained by large bureaucracies or legacy infrastructure. This makes them both nimble and scalable — precisely the characteristics we should prize if we care about outcomes rather than appearances.

What is holding them back? Zoning laws, facility regulations, funding gatekeeping, and the overbearing presence of standardized testing as the dominant measure of school quality. These constraints have erected an artificial scarcity of educational models at a time when we should be expanding choice and innovation.

The education policy world has spent the better part of two decades fixated on “accountability,” often defined narrowly through standardized test scores. The intention was good: measure what matters, and schools will improve. But the result has been a calcified, test-centric approach that discourages experimentation and undervalues broader human development.

Standardized tests capture some useful information — especially in early literacy and numeracy — but they are a poor proxy for what we actually want from education: curiosity, resilience, communication, collaboration, initiative, and civic understanding. The most important things we want schools to instill are often the hardest to measure — and therefore the most neglected. What if we broadened our aperture?

An abundance agenda for education would embrace the same richer, more multidimensional view of student success that is currently used by private schools today. It would include academic progress, measured with test scores, but also track real-world readiness, student engagement, and family satisfaction. This can be done today with any of the third party accreditation agencies that already provide learning and assessment processes for thousands of k12 schools across the country.

With accreditation as the tool for understanding the efficacy of these new school models, state policy makers should embrace policies that lead to more schools and more school models.

This vision is not pie-in-the-sky. States like Arizona and Florida already have universal Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) that allow families to fund non-traditional schooling. In AZ, Families can access up to $7,500 in state funds for educational programs like Outschool, or a microschool like KaiPod Learning.

Families choose microschools for more personalized learning, or because of school safety concerns in a world of too many school shootings and too much bullying. From what we see, and from the families that choose these new education pathways, the early results are promising: more families are opting in, providers are proliferating, and student engagement is rising.

Keep public schools open, widely available and free. Keep focused on relentless improvement and reform to improve public education for all. And, focus a policy agenda on removing roadblocks and improving opportunities for families of all income levels to have the choice to opt out of this free option and choose an independent school if they prefer. As in Florida, Arizona, and twenty other states, parents should be able to take a fraction of the per pupil amount the public school would earn from having them attend and allocate it to any educational provider they deem best for their child. Provide tools for accrediting agencies, and others, to develop wider scorecards of school success, broadening beyond just test scores.

Abundance in education means removing barriers to entry, rewarding those who produce value, and creating room for new institutions to emerge. We need to build. More schools. More diverse models. More accountability to families rather than bureaucracies. More ways of measuring success that reflect the complexity of human development.